Mystery Card #4

Mystery Card #4

The River was turning gold as Maggy meandered along the LaZell Bridge. The clouds above, the color of sun-drenched parchment, dotted the golden sky. Maggy’s bag was rattling and whumping behind her on two ancient wheels that had nearly worn away over time. The bag was a blotchy brown and grey, over-sized and lumpy, but it was hers, and she loved it almost as much as what was inside it.

Maggy was starting to huff and whump, herself. A large canvas painting was held in her right arm, tucked under her moist armpit and held in place by increasingly stiffening and tiring joints. The painting was of her father, a stern man in a blue tunic, pale face and paler eyes above a vibrant orange beard, his fierce stare somewhat diminished by a bright yellow pork pie hat. In truth, it was a likeness of a likeness. Maggy’s father had died of fever when she was two, and this was a copy of a portrait his good friend Matilda Savorre had made, only three days before he died.

They had called it a mysterious turn of events. In his youth, Tomas Vellenorn had been a beautiful man, but the demands of manhood had proven too great a burden for him. A few short years at a tannery had furrowed his brow, thinned his lips (necessitating the beard), and stooped his shoulders. Tomas and his handsome wife Eleanor had been of a height when they wed; Mama used to say how much she loved being able to kiss her beloved without having to stand on tiptoe or draw him down to her. Toward the end, when she had to dip her head to kiss him, she had become markedly less generous in her praises. Of course, they did not kiss much, during the two years that all three of them were walking the earth. Most everything Maggy knew of her parents had been learned from neighbors.

By the time Maggy was born, they had both strayed from their vows more than once. Gossips used to suggest that Maggy’s real father was the brawny baker’s son, Jean-Perlo, but Maggy’s slim figure and fiery hair proved them wrong. For better or worse, her father was Tomas Vellenorn, a tortured, beautiful, useless, dead man.

The sky was darkening to a glimmering bronze as the sun slowly dipped. Maggy took in the smell of aging bread from Gierne’s to the north, the rolls he was invariably unable to sell since the customers always preferred his croissants in the morning and his baguettes in the evening. Gierne kept baking his rolls, though; he said they were his favorite. The odor of his pet passion danced daintily along the river and floated over the bridge, mixing with the intoxicating vapor of the tiny arboretum from the northwest: peonies, lilies, and nasturtiums pirouetting around the old bread, giving it new life. The breeze was light, undemanding, yet it offered so much to those who crossed the LaZell Bridge.

It was an excellent mask for Maggy’s lumpy old bag. She called her bag Papa Tom, and it smelled like death. She had owned the bag for many years now, and the smell was fading, but without question anyone who knew Maggy knew that odor, and anyone who met her was soon introduced. Her Mama had demanded that she keep it out of the house, but any time Maggy left her home, Papa Tom came with her. It was as much a part of her as her Mama and her house.

When Maggy was halfway across the LaZell, she heard a clicking far behind her. She glanced over her shoulder, without a care, and saw a tall man in a black frock coat, absently looking toward her, not at her, as he casually crossed the bridge. His heels had been clicking, but he had adjusted his gait, and was now walking silently, a vague smile on his face, glancing everywhere but at Maggy, as he crossed.

Papa Tom skittered slightly, having rolled over a small stone. Maggy stopped to kick the stone lightly into the edge of the LaZell, where it nestled comfortably between the smooth flagstones of the bridge and the rock-and-mortar of the waist-high walls, at rest. Maggy offered a faint grin and continued on her way.

Another click sounded behind her, but Maggy did not bother to look. She knew who it was.

She was only four when Mama had first begun to warn her of strangers. They lived in a prosperous town, and many visited to cross the bridge, the admire their tiny arboretum, or even to attend Elaine’s painting studio, the largest and best provisioned in the area. Maggy always met new people when Mama took her to the market, which was often enough once her grandmother had become bedridden. Grandmama had been unbearable when she was well, and her rapid collapse had made her no more pleasant a conversationalist. When they were out of the house, Mama was a charming and diverse socialite. She was polite to the poor, engaging to the wealthy, and alternately warm and firm to the burgeoning bourgeoisie. She would show Maggy off in new dresses to endless praise, and as a child Maggy had grown accustomed to this celebration. When Grandmama died, though, and Maggy grew old enough to go out on her own, everything changed.

Mama was terrified that someone would take Maggy away. One time, a man in the market grabbed Maggy’s shoulder, and Mama accosted the man brutally until he fled. They never saw the man again. It was unusual for strangers to visit the market, but not unheard of; he must have been a stranger.

Maggy never understood, though, where this terror had come from. She sneaked out of the house many times, and Mama would chase her down, looking frazzled and causing a scene, and they would bellow at each other past nightfall. Finally, after two years of screaming and defiance and even the occasional cruel word, Mama relented and allowed Maggy to go out on her own, to learn painting visit the flowers and even to go to the market alone sometimes. But she always took Papa Tom with her.

A third click sounded, and Maggy stopped. She was nearly to the end of the LaZell, but still. It had to be done. She set her portrait against the waist-high wall of the bridge before leaning against it herself, glancing out at the river, and casually looking back over the flagstones. The strange man was much closer than he had been, despite his casual gait.

He was tall and thin. Though all in black and a bit morbid looking, he was attractive and well dressed. The silken half-cape over his suit made him look like a fashionable city-dweller, and his cocked hat gave the impression of an incorrigible rake. Maggy did not doubt she could have many adventures with such a fellow; that he would charm her, worship her, love her, and ultimately break her heart. It would inspire some beautiful art, yet it would be beautiful by itself as well. She sighed, very lightly, as she bent down and opened her bag.

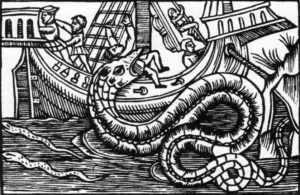

Papa Tom was fastened by two separate threads that wound around two separate buttons, one black and one green, that looked the slightest bit like eyes on some bloated toad. When Maggy unwound the buttons and opened the flab that secured the overstuffed bag, it gave the distinct impression that the toad was opening its mouth to snare a fly. Maggy did not rummage in the bag, nor did she favor the stranger with another look. She leaned against the waist-high wall again, and looked out northwest toward the arboretum.

The clicking returned, this time constant. The strange man had stopped hiding his intent, whatever it was, and was now striding confidently toward her. He could be holding a pistol, or a flower, or a paintbrush she had dropped, or his outstretched hand. It did not matter.

The man was very close. He took a breath to speak. Maggy kicked at Papa Tom idly, and something clattered out of the overstuffed bag. She heard the man’s voice catch, and sense him glancing down at at the flagstones.

A long silence followed. Maggy and the stranger looked at each other. Words had evidently failed him. Maggy did not have much use for words these days.

The stranger turned and walked away. She would never learn what he wanted.

Maggy bent down and picked up the arm. It was only bone now, pocked with mossy green growths that may have once been flesh. Once upon a time she had held it fondly before placing it gently back into the bag. Now, she unceremoniously jammed it back in place and wound the bag shut. It gave the impression of a fat toad closing its jaws over a satisfying meal.

Maggy went home.

It was only just past sundown, but there was a good chance Mama would be sleeping. Maggy opened the front door slowly, spacing out the obnoxious creaks. Someday, they would oil those hinges. Still holding her portrait under her armpit, she waddled through the kitchen and into her cramped bedroom. Even though she rarely cooked, Mama insisted on keeping the stuffy upstairs room to herself, where Grandmama had lived and died. Maggy’s bedroom was larger, but it was filled with paintings.

Everywhere she looked, Tomas Vellenorn stared back at her, drawn and worn down, poorly attempting to look imperious. There were no imaginings of his beautiful youth, nor copies of his older work modeling for Matilda Savorre back before Maggy was born. There were attempts at different angles, and many different idle plays with color, but they were all the same man, staring out at her, trying above all to maintain his dignity.

Maggy set Papa Tom in the one free corner, then lay the new portrait against a stack of long dried twins. From under her tiny cot, she drew a sheaf of pasteboard and her charcoals. She sat on her cot, charcoal in hand, pasteboard in her lap, and looked at her father. Faintly, she could hear Mama snoring, as ages ago she could hear her grandmama’s moans.

Maggy turned her face away, down at the pasteboard. She began to sketch the outline of a tall man in black, beautiful and terrified, being drawn like a fly into a fat toad’s mouth. The toad looked very satisfied.

Mystery Card Writing. #3

Mystery Card Writing. #3 Mystery Card Writings, #2

Mystery Card Writings, #2