So, I played video games a lot as a kid. I didn’t have a lot of friends, so the games that demanded time and emotional investment were the ones that engaged me the most. The best thing about video games is that if you try hard and practice, you will succeed; every time. It’d be nice if real life were more like that.

Probably the most formative game of my youth was FF6 (or FF3 here in the US). It had an engaging story line, pretty strong JRPG gameplay, customizability, outstanding mood (a la Poe’s Poetics on Mood) and great music (and graphics for the time). Most importantly though, it had a large cast of developed characters with some great arcs. More than any book, these characters helped get me through my younger days and make me the guy I am now.

I don’t derive much inspiration from truisms, sports, or kitties. I get it from pixels.

S’like, here’s a few of them now.

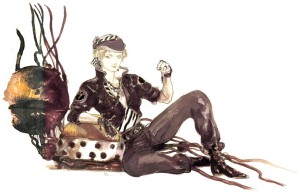

1. Locke.

Locke was the first video game hero I knew who was not a soldier. My first game in the series was FF4, starring Cecil the knight and his friend Kain the dragoon: non-melee roles were relegated to ancillary men and female love interests (Rosa used the usual bow-and-arrow, and Rydia shot lightnin’ out her hands).

Of course, in a game about killing monsters, it’s only natural that big guys with big swords take the limelight. In FF1, though you could essentially design your own team (including Locke’s predecessor, the Thief), it was foolhardy for a new player to put anyone in front other than a Warrior. Locke certainly kills as many monsters as anyone else, and at his strongest he’s swinging the same swords handled by the war-mages Terra, Celes, and Edgar. BUT, his identity, the archetype that defines him, was an adventurer, a thief, someone who uses his wits rather than his muscles to overcome obstacles. And while we didn’t see much of this in the actual gameplay, that was the archetype that made me identify with Locke before anyone else.

Despite being a thief (or “Treasure hunter” as he vehemently put it), Locke was an ethically generous volunteer. Due to a tragedy with a former love (that also echos a rather emo-ish episode of my own life), Locke immediately volunteers to help people in trouble (mostly female people), never asking anything in return. And while Locke’s eventual relationship with Celes may well reflect the “Nice Guy” trend found in modern culture, Locke never demands reciprocation; nor, technically, is any given during the run of the game.

I didn’t have any role models growing up, certainly not any real ones. Locke was the first person from whom I consciously gained an ethical and social compass.

2. Celes.

Celes was my favorite, and was always in the lead whenever she was in the party. From as early as I can remember (which is probably this right here), I have appreciated confident and assertive women. If anything, FF6 taught me that such women were not just cliched ornaments to be won by men.

See, here’s the beautiful thing about Celes. She starts out as something entirely typical: a Strong Woman to be won over by the Nice Guy (and that typicality is even commented on in the game). Things start adversarially, the two are thrown together, she denies any interest in him, they grow slowly closer, a villainous deus-ex-machina drives them apart, and they reunite. All this happens in the first half of the game. Then, in the unprecedented second half, suddenly, Celes is the lead.

Even in the first half, Celes has more of a story than many others. Raised as a soldier, ‘surgically implanted’ with magic, she speaks out against the imperialist regime and is imprisoned. But unlike many other characters (especially those that appear as late as she does), her history continues to be relevant throughout the plot. Cyan, Shadow, Sabin, Gau, even Edgar: they all become essentially interchangeable after the Battle for the Frozen Esper, and their various character arcs are only revisited in (often optional) cut scenes. And while you could (justly) argue that this is an attempt to let Locke overshadow Terra (the female protagonist), the Second Half of the game flips this on its head.

Suddenly, we’re following Celes alone. Lost on a tiny island in a dead world with her only father-figure slowly dying in front of her, Celes’ struggle with suicide and her ultimate decision to cling to hope and move forward with her life reflects an emotional strength way ahead of its time in video games, wholly beyond the hack-and-slashing or sarcastic-attitude associated with Strong Women of contemporary pop-culture.

Celes is easily the most heroic character of this game. She loses absolutely everything in the Cataclysm, all thanks to the machinations of Kefka, one of two men who were the closest thing she had to brothers. And from that place of absolute despair, she picks up and reassembles her army, her friends, and stands against the Evil Clown; not to magically transform the world to the way it was, but just to allow everyone to start rebuilding.

3. Kefka.

Kefka is the evil archetype we all love to hate. Like Richard III or Skeletor, he’s an unapologetic villain who’s immaturity and clever one-liners leave us silently rooting for them, even as our true heroes fight against them. Mad, bad, and loving it, Kefka’s a villain’s villain, and as the old FF adage goes: “Sephiroth tried to destroy the world. Kefka succeeded.” Though, a more accurate adage would be: “Sephiroth tried to become a god. Kefka succeeded.”

Although Kefka and Celes are essentially siblings-of-fortune, the Mad Clown has almost no back-story to be found anywhere. The only info you ever get on him is found in a pub: “Here’s one for you! That guy Kefka? He was Cid’s first experimental Magitek Knight. But the process wasn’t perfected yet. Something in Kefka’s mind snapped that day…”

And in that one line, his entire personality is thrown into dramatically different light. What was Kefka like before this experiment? Would he have committed any of the atrocities he did if not for this alleged mistake?

In a recent Atlantic online article, neuroscientist David Eagleman discusses the well-established but still not respected notion that human decisions are dictated (perhaps exclusively) by biological influences that they cannot control. He discusses a mass-shooter who felt certain there was something wrong with his brain: there was. He discusses a pedophile who’s aberrant behavior (and desires) arose due to the growth of a massive tumor in the orbitofrontal cortex of the brain: removal of the tumor eliminated the aberrant desires and behavior.

While it is an obvious truism that we must take steps to prevent harmful behavior, we still have to ask ourselves to what extent is anyone ‘morally’ responsible for their behavior. Eagleman’s article immediately made me think of Sam Harris’ book Free Will, which he covers in its entirety on Youtube.

Kefka complicates this issue further: his very first action in the game is to mentally enslave the lead character Terra using a “Slave Crown,” and force her to fight and kill innocent people. Terra feels guilty after being freed, but everyone else instantly forgives her: she had no control over her actions. But once (if) we learn of Kefka’s origin, what control did he really have over his?

Kefka taught me that judging anyone is an extremely muddy business.